Wren: “A body I can embody“

The artist speaks with Gender Defiant about birds, top surgery, bodybuilding, and parenting with love

Wren is a queer artist, activist, and educator who spent 20 years as a teacher working with children who were learning about identity, being out, and coming out. Gender Defiant caught up with them during their recent exhibition Associated with Heartthrobs.

Gender Defiant: Your paintings The Alphazone and Spaceship each have a human torso with a bird’s head. In Spaceship [below], the bird looks like a hawk, with a strong, confident expression. The bird in Alphazone [above] has a softer face. Tenderness atop a gym body.

Wren: Alphazone….I fucking love that bird [laughter]. It’s a pigeon.

GD: That pigeon is ripped.

Wren: Pigeons carry a surprising depth of meaning. Quietly going about their business in cities and countryside alike...

GD: As trans people have always done...

Wren: Some of us not so quietly! And that is a Thank You to all those who fought and continue to fight for human rights. But on strength and tenderness, Alphazone leans into one of my current deep dives. How can softness show up in our power, how does it look, feel, sound, smell....It has been a central question in my life and who I am, right now.

GD: Speaking of power, the white leotard in Spaceship reminds me of Olympic gymnastics.

Wren: The leotard is a play on gender expression, and the impression of. What people get from how I design or costume myself. What is expected to be covered and what does not have to be covered.

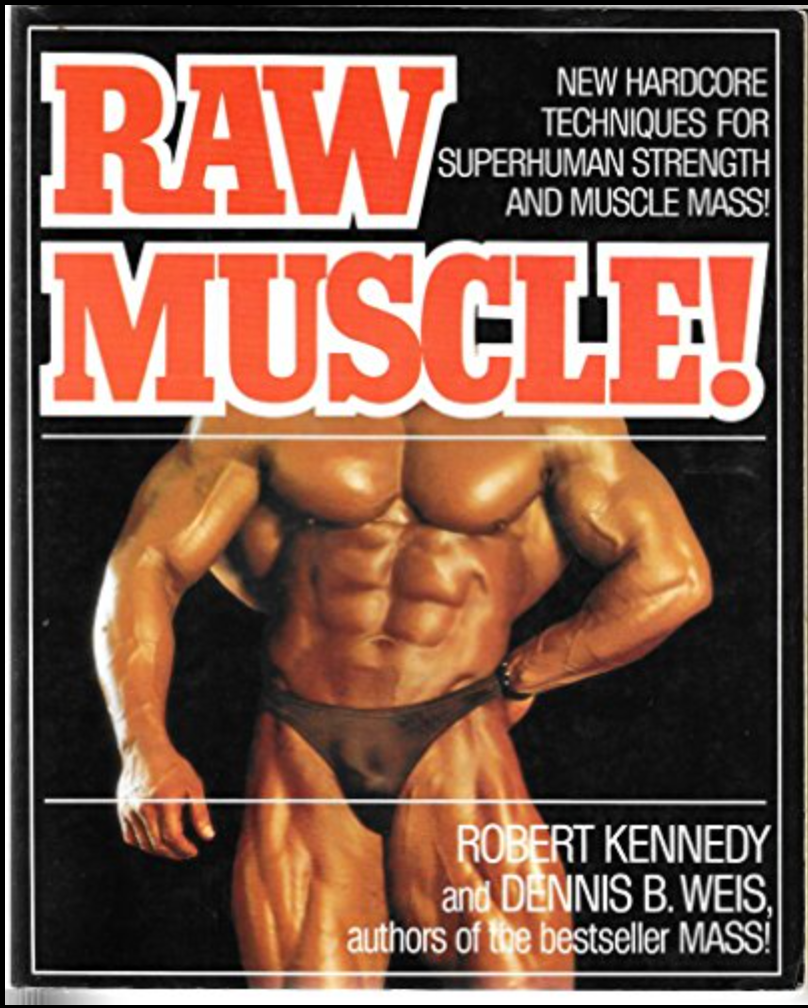

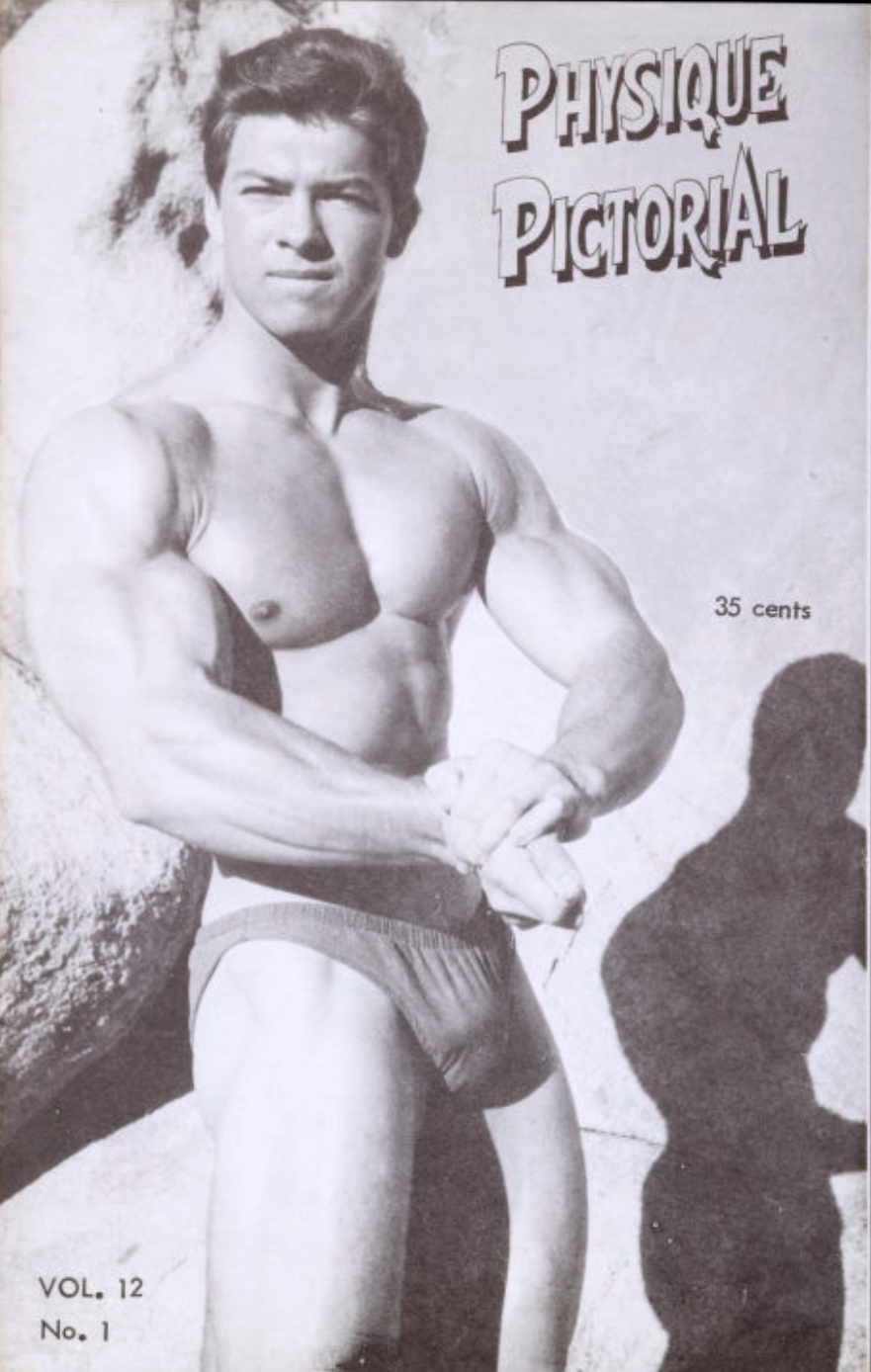

A lot of these paintings were influenced by Raw Muscle, a book of vintage bodybuilder photos, and by Tom of Finland’s images in Physique Pictorial, a magazine of gay erotica from the mid-20th century.

The beefcake magazine has the same bodies, in the same poses, as the bodybuilding book. I wanted to play with that irony.

GD: Alphazone nails that irony. An ultra-defined body with a sweet pigeon face and a towel jauntily flowing. But how did you come to birds to begin with?

Wren: Oh god [laughter]. Everyone asks that question, and I’ve avoided answering it for so long. Birds showed up in my paintings before I knew why. I was ready to set them down. But before the show, my gallerist kind of suggested I make more paintings with birds, as they seem to be popular. Now I am tasked with: can they come with me, and why? Birds reminded me of that dreaded saying ‘if you love something set it free. If it comes back it is yours, if it doesn’t, it never was’—the possible trueness of which paralyzed me in relationships, including my relationship with myself. AND that’s enough about that.

GD: Well, your name is Wren. [laughter]

Wren: Yes it is. This name goes back to a nickname my first secret love gave me—nothing to do with the bird.

GD: You have had two top surgeries. What was it like walking into a surgeon's office for the first time?

Thank you for your support as a free subscriber. It means the world to us. Will you consider upgrading to paid to help underwrite our expenses?

Wren: I thought it was just going to be a conversation [laughs]. Instead I was given a gown and told to undress from the waist up. I was handed a menu of choices for nipple locations and shapes within a binary: masculine or feminine. They did a photo shoot of my breasts from all angles. Honestly it was the first time in a long time I felt like hiding my chest.

GD: Had you done binding?

Wren: I had never spent time binding. I wore my breasts like a uniform. Which definitely put me at odds with my sense of self.

GD: I wonder if surgeons tend to assume that breasts trigger self-hate or suicidality in every trans masc person who walks through their door.

Wren: I cannot speak for all surgeons, or even one. In my experience, many cis people, including doctors, believe that transitioning means simply woman to man, or man to woman. But gender is much bigger. People are so much bigger than that binary. The nuances of each individual are up to them, in them—this is a big part of why finding the right surgical team is so important. We want them to hear us and see us, sometimes even before we can. We need them to collaborate with us.

It took me a while to accept both the masculine and feminine in me. At first I wanted to withhold gender from myself. Ungender my movements, my behaviors, my expressions, and so on. Eventually I came to understand masculine and feminine as energies, not qualities. I believe we do not have to make ourselves readable to others. We do not have to make our gender understandable for others’ ease. I identify as trans non-binary.

We do not have to make ourselves readable to others. We do not have to make our gender understandable for others’ ease.

GD: Did you feel a sense of loss after top surgery?

Wren: I worked with a somatic therapist before my first surgery. We did an exercise where I held my fears about top surgery in one hand. Imagined their texture, weight, size, shape. I imagined my hopes in the other hand and did the same. Then I moved my hands closer and closer together to see if my fears and hopes could live together. I woke up with only HOPES. And I had processed the fact that my breasts had done their job. They nursed my baby.

So I did not feel the specific loss of breasts. However, I did feel the loss of connection to their movement. I experienced dysmorphia for the first time, and loud. What I communicated, or hoped I communicated, to the first surgeon was not alive in my results. I couldn’t shake the feeling that I still had breasts—now very awkward breasts.

After the second surgery, I understood loss differently. I felt the loss of time—all that time dealing with a body I wasn’t invested in. When I was around 8 or 9, my sister pointed out my new budding breasts in front of my whole extended family. It was humiliating. That moment felt like a betrayal by my body and my family. I went into hiding within that “female” body. Until that point, I had been living as a boy. I was a boy.

My second top surgery put me back into a body I can embody.

GD: Back to your paintings: There are two nudes in The inner child has talents of their own. One has breasts and closed, almost clenched hands. That figure pulls inward, away from a viewer. The second nude has lines on the chest, not breasts, and open hands gesturing upward. It runs toward a viewer, jubilant. Are you both of these figures?

Wren: I am neither [smiles]. The figure is my lover, my partner, on a night we ran together naked into the snow. It was a full sensory experience of play and excitement. This painting is a moment of ALIVENESS. Of getting out of the way of whatever is standing between you and your euphoria.

GD: What’s your advice for parents of trans kids?

Wren: Ask your child how they want to be cared for. And how they would like you to be involved. Not just one time, but regularly. Check in with them. They don’t owe anyone a “coming out.”

Listen to your child with curiosity.

Be humble. We don’t know more about them [our children] than they do.

Educate yourself alongside your child, learn about things together.

An important thing to keep in mind is connections—to other trans people your kid’s age, trans adults, organization and activities. Two places to start: the resources page at the Trevor Project and PFLAG.

_____

To view Wren’s full exhibition Associated with Heartthrobs, contact Zynka Gallery to request a catalog.

At Gender Defiant, we recognize that trans art matters more than ever.