Wednesday Essay: Whitman's Time Machine

This country is so confusing. So much so, I find myself profoundly moved by the idea that a time machine might someday be invented.

I want to get off the forward moving train that is time because I can’t see what’s around the bend. I want to go to the dine-in movie theatre, eat burgers and fries, forget I turned vegetarian— watch bad movies that feed me a bunch of bullshit and not think about the damage.

Where would you go if you had a time machine? It’s something to think about. I would much rather have a time machine and / or the transporter by which to teleport than AI. We need a better technology. Maybe I’m depressed? Maybe I feel helpless? Wanting these things . . .

I haven’t been with JJ for several days because of work. I’ve been far away from Maine, in New York, a place where a lot more seems possible, even if it’s unduly stressful. There is a great variety of people here. These people travel together in masses. They tolerate sharing closed spaces with one another. There’s something lulling about how you’re constantly on the move with others.

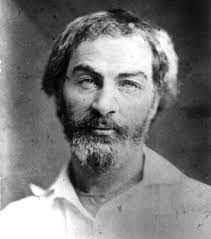

I realize I know where I want to go when the time machine is invented. Straight to Manhattan in 1856 to hop on the Brooklyn Ferry with Walt Whitman. I want to be there with him, watch him up close seeing us as he sees us in his poem “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry,” encounter first hand his love, empathy and knowledge of our individual and collective power.

“Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” encompasses the activity of the Harbor, the ships and their workers, the wind, the birds, the water— it is a veritable catalogue of the experience. I took the Staten Island Ferry four times today. The way Whitman describes the experience is “relatable,” as my students might say. Riding the Ferry is an intensely peopled experience.

And so, while I was longing for a time machine, I failed to notice I had one right in front of me. Whitman’s poem is a time machine, as many poems are.

We recognize Whitman’s power and influence now, but his views were considered controversial during his lifetime. In drawing our attention to 20th century Black American poet June Jordan’s appreciation for Whitman, critic Lavelle Porter reminds us that “respectable men of letters in his own time found his work insufficiently literary, obscene, and perverse, and only later was he provisionally included in the American literary tradition.” In this article, Jordan is quoted as stating that Whitman is “the one white father who shares the systematic disadvantages of his heterogenous offspring trapped inside a closet that is, in reality, as huge as the continental spread of North and South America.”

Maybe what I love about Whitman is that he doesn’t let things like this get him down. In his work, he is consistently (and constantly) drawing our attention to everything that is beautiful and intricate in day-to-day operations of the world that many would consider the “grind.”

In a time when I feel not just divided, but deceived, by public discourse, the generosity of Whitman’s gesture, his acknowledgment of beauty, feels good. And it feels queer.

One of the points our poet drives home in ‘Crossing Brookln Ferry” in that we are all one as a people across time. Whitman *knows* he is speaking to future readers of his work. He is intent on creating intimacy with his reader. Time can and will not come between him and his reader. It’s empathy to the max.

[I’m putting the quotes from Whitman’s poem in italics here because Substack —hello, MLA guidelines??? — is not allowing me to indent the requisite five spaces.]

What is it then between us?

What is the count of the scores or hundreds of years between us?

Whatever it is, it avails not—distance avails not, and place avails not,

I too lived, Brooklyn of ample hills was mine,

I too walk’d the streets of Manhattan island, and bathed in the waters around it,

I too felt the curious abrupt questionings stir within me,

In the day among crowds of people sometimes they came upon me,

In my walks home late at night or as I lay in my bed they came upon me,

I too had been struck from the float forever held in solution,

I too had receiv’d identity by my body,

That I was I knew was of my body, and what I should be I knew I should be of my body.

So, too, Whitman knows that one receives “identity” by their body. (This is something many wrestle with, obviously— BiPOC folk, trans folk, women, etc.) I find this interesting because it acknowledges that the bodies we are born into influence our how we are perceived and how we come to know our own power or lack thereof.

It is not just that Whitman is fixated on the sheer physicality of our lived experience. It does not need to be read as sexual. It is, as I read it, that we are born into our bodies, and that their appearance (identity) can and will shape our lives. Like us, Whitman acknowledges that he:

Play’d the part that still looks back on the actor or actress,

The same old role, the role that is what we make it, as great as we like,

Or as small as we like, or both great and small.

Whitman doesn’t dig binaries. In his mind, we’re all made of the same fabric. Our consciousness is one. If it is occurring to you that Whitman and MAGA Republicans are polar opposite, you are correct.

Because Whitman is about inclusion and love. Whitman is about joy in community and experiencing what he envisions as the beauty of America and its people.

What would Whitman think if he were facing, as we are, the precipice of November’s election?

I think he would see it through. I think he would stay the course. I have to think that, because he lived through the Civil War and volunteered as a nurse for wounded soldiers.

What we find perilous now, he found perilous then.

Comments ()