Three Nightmares and a Picnic

In Mexico City, more bumps on the road to gender care for JJ

The only two white people

The water dispenser is at the front of the lab waiting room. Instead of cups, there are paper cones. JJ is told they have five minutes to drink 18 of them. The cones, flimsy as flower petals, fold if you hold them too hard.

I start counting, bringing JJ five cones of water within two minutes. I am then determined to bring five more. But JJ says they are feeling sick, they don’t want to drink so much water all at once. My father’s daughter, I am instantly frustrated. Why can’t JJ consume all 18 in the required five minutes? The cones hold barely a sip!

Gender Defiant brings you stories about parents raising trans kids—stories you won’t get anywhere else. Please consider a paid subscription:

JJ whispers that they are uncomfortable because they stand out. They can sense people looking. “No one cares!” I say, once again channeling the father I stopped speaking to a few years prior to his death, “These people have their own problems.” I tell JJ they are imagining things.

JJ points out that we are the only two white people in a room of some 50 patients. I look around. JJ is not wrong. Everyone except us is brown.

To me, the lab waiting room is like the subway platform in New York. We are in good company. Everyone here is suffering together, equals. But while I spent much of my adult life living in NYC, JJ has lived the majority of their life in a tiny New England town. The whitest place ever.

Racism exists in Mexico city. Not directed at us so much as between people who are darker and lighter shades of Brown. The racism here is starker than in America, yet hard for me to see, accustomed as I am to my own lens. My urban American lens. And JJ, a trans person attuned to being clocked as an outsider, sees different things than I do. It is very possible we are being stared at.

I return to JJ with two more cones of water only to be met with a look of quiet fury. They’ve had enough. They are ready for their pelvic sonogram.

In the dark sonogram room, cold jelly is being applied to JJ's lower abdomen as they lie on the table. JJ says, “Don't look.”

I keep my eyes closed until it’s over.

Mad at everyone

After the sonogram, JJ needs to pee. Did I actually expect Mexico would be some nirvana with gender-neutral bathrooms wherever I turned? In Mexico City, even Starbucks, the northern light of individual, gender-neutral restrooms in the United States, has gendered bathrooms. And, I am very sorry to report, so does Condesa Clinic, where we are trying to get JJ enrolled for gender-affirming care.

A restroom is just a room, I fume as we leave the lab. It's amazing how the absence of this smallest of spaces can so completely and effectively assault one's dignity. And ruin the day.

I am mad at the people who want to keep my kid out. I hate the time finding a restroom JJ can use takes up. I am mad at JJ. I am mad at everyone, and I am ashamed that JJ sees me mad, and that JJ has to endure this idiocy in the first place.

Then I pivot. I order an Uber that shuttles us quickly to a very queer hair salon where JJ not only accesses a gender-neutral bathroom but has their hair cut by a trans stylist.

A grimace, a terrible laugh

With sonogram results in hand, we arrive at the Condesa gender clinic for our evaluation with Dr. Gael Valaquez, the psychiatrist. He will decide whether JJ gets admitted to the clinic for ongoing care, which we very much hope for.

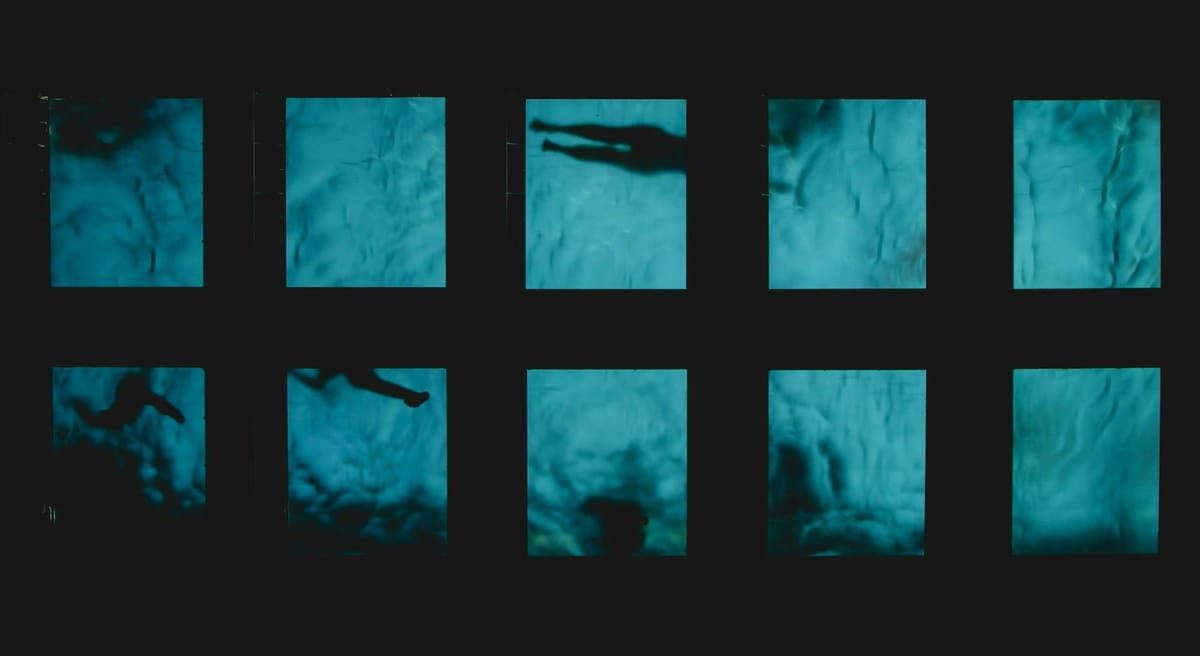

Dr. Valaquez reviews the typed lab results and consults the images. He stares at the pages, shuffles them, looks back at certain images, all while looking increasingly startled and disconcerted.

We watch his face. At first, its surface is unbothered, wearing the relaxed skin that belongs to eyes receiving information. Then the eyes widen in alarm and the skin draws back. The lips assume a grimace, on the verge of a terrible laugh.

The results of the pelvic sonogram, he says, are impossible. The sonogram shows a prostate. A thing JJ does not, and cannot, have.

The results of the pelvic sonogram, he announces, are impossible. The sonogram shows a prostate. A thing JJ does not, and cannot, have

“I will never trust results from Salud Digna lab again!” the doctor roars.

“Am I intersex?”

When Dr. Valaquez points at the blur on the black and white film and pronounces it a prostate, I realize something that is probably obvious to most. A layperson does not have the training to read a sonogram. If Dr. Valaquez had pointed at the blur and declared it an opossum, I could not have refuted him.

Thus I find myself poorly equipped to respond to JJ when they fret aloud, “Am I intersex?”

The knowledge that there is so little we can actually know about what is going on inside our bodies makes me queasy. I tell JJ to set any anxiety aside until we meet with Dr. Rivera the following week.

Dr. Rivera, their private gender doctor, echoes Dr. Valaquez’ suspicion that the body in the ultrasound images does not belong to JJ: we must have been given someone else’s films by mistake. (I seethe, quietly plotting my return to Salud Digna to demand an apology and a refund.)

We schedule a re-do of both ultrasounds in a few weeks, after which—finally—JJ is officially made a patient of the Condesa gender clinic. For the first time since we arrived in Mexico, they receive their testosterone as a prescription; till now, we’ve been buying it over-the-counter at the farmacía.

Here, one has more choices for how they prefer their hormones to be administered. JJ was using a nightly topical gel, but now they have chosen an injection, which they’ll get every three months. And Dr. Rivera has lowered their dose slightly to alleviate JJ’s acne.

When I asked about lowering JJ’s dosage in the U.S. to address side effects, Dr. Chanoz dismissed my concerns. It turns out that with hormones, like many medications, adjustments in dosage and application can be helpful and even necessary.

I don’t feel so much validated as relieved.

We know no one, and we are shy

The Condesa clinic’s Picnic welcomes trans kids and their families.

As JJ and I approach, we recognize the group by the Progress Flag they have spread out on the grass alongside the pink and blue Transgender Flag.

Because we know no one, and we are shy, JJ and I approach the group quietly.

A woman spies us and turns to welcome us. She leads JJ to a group of teens by the picnic tables and then introduces me to a group of older folks. I recognize them. We are the parents, partners, the loved ones. The group is entirely made up of Mexicans, yet it feels just like PFLAG back at home. Safe.

We take turns sharing who we are and why we are here, and while they are speaking in Spanish, something miraculous happens: I don’t understand everything they are saying, but I understand a lot. Can it be, after months of study with a tutor, that I have finally learned to listen to Español?

When it’s my turn, I abandon English, leaning instead on my new Spanish to help me say what I mean.

Yo estoy muy contento aquí. Yo estoy con mi gente.

It’s the worst Español ever. But I can see they understand!

I am with my people.

—T.C.

Did you know a paid subscription of just $10 a month helps trans youth seeking care? Please consider upgrading: