“But you’re safe where YOU live, right?”

Even in a sanctuary state, safe for who is a question, and safe for how long is another. JJ and I are planning to leave the country.

I wasn’t thinking about trans rights when I moved with my then six year-old to the state where we live, a sanctuary state that protects trans people’s right to gender affirming care. It would be another five years until my child would even come out. We didn’t know how lucky we were to land here.

Before I moved to this state, I applied for a position at a university in Florida. It was exactly the type of job I’d been hoping for all my life, and I had no problem with Florida. There were alligators, horseback riding lessons for my kid, beaches, affordable midcentury ramblers I could hope to buy, and enough midcentury modern furniture left behind by deceased seniors to turn my ramshackle hermitage into a personal heaven.

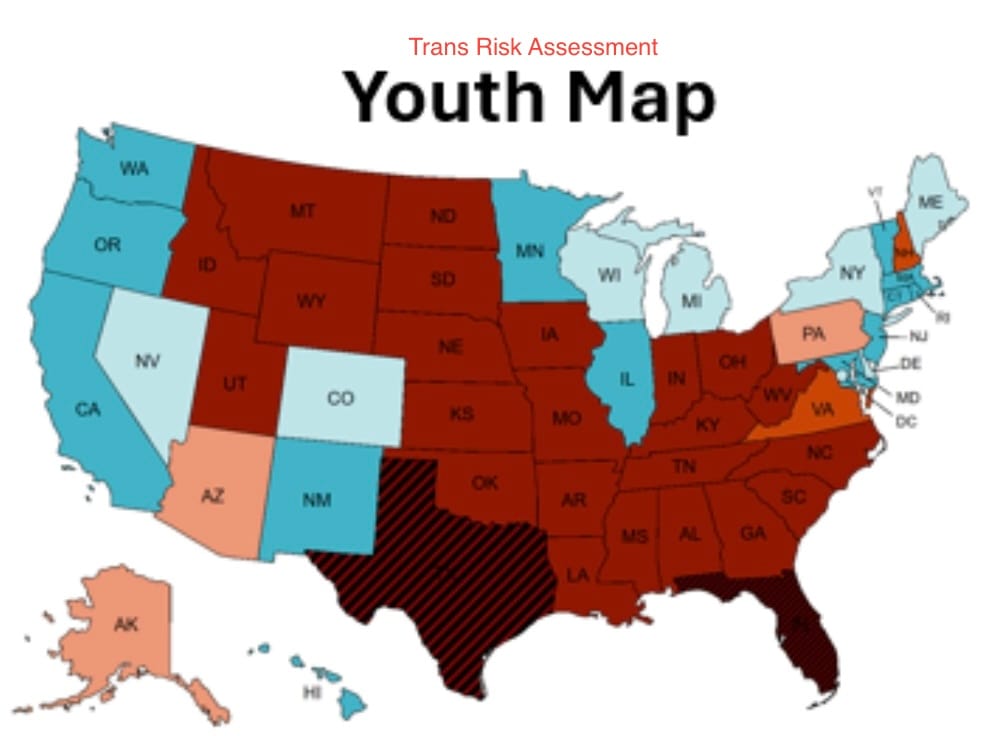

I didn’t get the job. Turns out that was lucky, too. When I recall my willingness to move to Florida, I shudder, imagining the panic I would be feeling right now as a parent. Lifesaving care for trans kids is banned in Florida (and banned or severely restricted in 27 other states). My child could be arrested just for washing their hands in a public restroom. Leaving is not an option for everyone, but because I have money and job flexibility—more pieces of luck—I would probably leave, as NBA champion Dwyane Wade left for the sake of his child, and as many trans folks in Florida are doing.

Unspoken assumptions

Around 40% of trans kids live in states banning or restricting their gender care, according to Human Rights Campaign. My child isn’t among that 40%. However—and here’s my personal update—JJ and I are moving out of the country.

I’m still in the research phase of this transition. I’m not sure yet where in the world JJ and I will end up, but we are getting ready, boxing up belongings and finding homes for our pets. When I share my news with friends, they tend to say: “But you’re safe where you live, right?”

Their unspoken assumption is that we are not affected by conditions elsewhere. They ask me questions to gauge whether JJ has it “bad enough” in their view, such as whether and in what ways and with what degree of severity JJ has been bullied.

The other day, I learned that my Gender Defiant colleague Noa Rabinow can no longer get hormones for her child in the Midwestern state where she lives—not a sanctuary state—because their health system cut off care for trans patients under 19. Noa has had to stockpile medicine, paying out of pocket for remaining prescription refills at great expense, and look for care across state lines. Meanwhile, kids in poorer families are being forced to detransition while doctors stand by helpless as hospital heads obey the Trump administration’s anti-trans executive orders.

Putting aside my friends’ peculiar idea that it's “fine” that my child can live in the body they are comfortable with while someone else’s child in a different state cannot, no state is a sanctuary if a national ban on youth care, or all trans care, happens. What affects one of us affects all of us.

Quaint

Whether we are able to move or not, all families with trans kids are having our lives upended. Lots of people believe the lies our presidential administration is spewing for political gain. The lie that trans people are dangerous and terrible. The lie that finding health care for one's children is criminal. The lie that our children’s doctors are “mutilators.”

What’s funny (or not) is that my past fears seem almost quaint in comparison to those I live with at present. I could never have imagined that I would come up against a fear so strong—ignited on learning that the passports of transgender individuals were being withheld—that I would choose to leave the country.

I started Gender Defiant two years ago to communicate to parents of cis and trans kids, and folks generally, about what it’s like to raise a trans kid. It is as joyful and ordinary as any parenting, but also uncomfortable for reasons having nothing to do with the kid or their transness but rather our larger culture’s transphobia.

By the way, I myself was part of the problem. I have been transphobic my entire life. Sure, I supported trans rights, but I didn’t know any trans people, and it never occurred to me that our freedoms are intertwined. I started Gender Defiant in part to document my failings and my learning and maybe inspire others to learn, too.

The burning center

Besides telling my story, Gender Defiant was my way of making amends to my kid and their people. So today, to mark two years of gender defiance, I am reposting the first Gender Defiant essay I wrote, in 2023, long before trans rights became the burning center of a moral panic.

A lot has changed in two years. The civil rights of trans people have deteriorated, but awareness of the “T’ in LGBTQ+ has grown. Nowadays, most folks know someone who is trans, know someone with trans family members, or have a trans family member. (My purely anecdotal guess is that at least 30% of our population falls somewhere outside the gender binary.)

Most of all, I wrote the essay out of love for JJ. It begins when they were 11. They are now 16 and recently got their driver’s license. — T.C.

GENDER DEFIANT

Originally published June 8, 2023

My kid is an “A” student whose favorite pastime is drawing cats. They have a pet tree frog named Gremlin. They are such a rule follower that once when I parked illegally on an empty street to take our dog for a quick walk, they refused to get out of the car. They have a strong sense of social justice. But they’re not perfect. I am currently annoyed with them for shirking their dishwashing duties and failing to scoop the litter box, and I’m considering docking their allowance this week. However, having been a fairly rotten teenager myself, I’m aware that I am profoundly blessed to have a child who’s so alert to how societal expectations should be met. I’ll confess: it’s baffling at times. Where did this child come from? They were lining their shoes up inside their closet at the age of three.

The day my kid turned 14, two people I encountered offered their condolences, each saying 14 was one of the most difficult ages to parent. We all worry. Are they eating healthy foods? Are they spending too much time in their room? Do they have supportive peers? Has their unfortunate and inevitable exposure to social media melted their cognitive abilities like cheese on leftover pizza in a microwave? Are they at risk of suicidal thoughts? If they are “individuating,” which therapists assure you is the healthiest thing a teenager can do, you can be certain they will not be sharing their innermost feelings with you.

When it comes to my kid, I have an additional burden of worry because they are trans.

Ghostly mushrooms

Early on during the coronavirus pandemic, my then 11-year-old kid, JJ, and I started taking walks together along the two-mile trail behind our house. It was spring, and every day that trail changed, gifting us a new discovery. We stooped to peep the ghostly mushrooms. We inspected wasp galls. We scorned the terribly behaved dogs that attempted to burst, barking furiously, through the electric fences that kept them corralled in the yards that edged the trail. Once we had to run from a bee swarm unleashed by amateur beekeepers who crossed our path in their otherworldly garb. We were trying to find a way to be ourselves in a strange time, and we mostly did that by talking.

What I did not realize then was that my kid was reorganizing their sense of self, and that this undertaking had likely begun before the pandemic offered up its surreal solitude.

Remember when COVID first hit and we were all afraid to go to the grocery store? Back then we’d use antibacterial wipes to sanitize the freezer door handles in the ice cream aisle. I recall vigilantly acquiring foodstuffs for JJ while they anxiously awaited my return. Homeschooling JJ wasn’t easy because it was so easy. The child has always been fastidious and absurdly competent. They would complete their day’s work by the time I’d had my second cup of coffee. Even remote gym class. JJ sprinted around the outside of the house the assigned dozen times. It was then that the afternoon hours gaped before us. More often than not, we decided to take a walk.

JJ and I let our conversations meander in the same manner we’d leave the trail to follow a creek. Alongside one creek’s glittering bottom shone a flash of blue clay! We took a bucket down there and dug a bunch of it up with a plan to sculpt something out of it. (We never did.) It was during these talking walks that JJ first came out.

My kid was gay! They didn’t come out as trans at first; they came out as pansexual. But what did it mean to be pansexual? I had absolutely no idea. I had to ask JJ. It turns out it’s not the same as being bisexual. It means liking trans folks, cishet folks, nonbinary folks and, well, anybody, really. I learned all of this during our walks through the woods.

Queer as Folk

I figured having a gay kid was going to be fun. And because I’d watched every episode of Queer as Folk on DVD back in 2003, I knew from the character of Debbie Novotny that I needed to get myself to a PFLAG meeting. This was easy enough given the newfound luxury of Zoom. I watched and listened to another mother speak about her child, who, in addition to being pansexual, was trans nonbinary. I nodded in recognition. JJ had taught me what those terms meant.

This mother expressed her frustration with family and friends who refused to use her child’s pronouns. “Until they can respect my child’s dignity, we won’t be seeing them,” she said. This translated to me as: They are dead to us. This was serious business. Wow, those parents with trans kids sure have it tough, I thought.

I realize now that I dreaded the possibility I might have a trans kid. While I knew my kid was gay, I tried to rule out the possibility they’d be trans. Which in itself was transphobic. At that time, I’d have said I didn’t want to face the problem of new pronouns. But what I really didn’t want to be burdened with was having my notions of gender completely undermined.

Authority figure

The reasons I didn’t want a trans child were manifold. First, their transness scared me, because I did not understand it. Being transgender was so out of my realm of knowledge that, frankly, it destabilized my position as an authority figure. As a teacher, I have become quite comfortable over the years with my role as the person everyone in the room assumes knows the most. But when JJ started speaking about different expressions of gender, I was lost.

All I could do was listen. And ask questions. And I would argue that one of the most affirming things you can do for your trans child, friend, or loved one is to listen. I cannot overstate this.

Here’s what I know now: my discomfort at having a trans child was rooted in fear. When you pick at gender norms even a little bit, they unravel like an ill-knit sweater. My fear rose from my inability to imagine a life outside conventional conceptions of gender. Once you start to look at how much every aspect of your life is shaped by gender norms, you begin to see how arbitrary and unhelpful these constructs are. But norms are norms, and deviation from long and widely held preconceptions causes discomfort. This anxiety and unease prevents so many of us from discovering how these ways of being and seeing have the potential to change us for the good. Why are we not open to seeing these expressions—nonbinary transgender, genderqueer, and all genderfluid identities—as potentially liberating, rather than threatening?

I confessed to my child’s therapist, a trans man, that I’d been transphobic in the past, and he responded, with humor, that he had been too! “Haven’t we all been transphobic?” he said.

“It doesn't affect me”

I know now that if I’m not doing the work to actively understand the perspectives of trans people, I am being transphobic. I know now that not thinking about it because “it doesn’t affect me” was transphobic. You may be reading this and wondering if you, too, are transphobic. I’m here to suggest that you cannot go on thinking you that you care about, or support, trans folks without knowing that you are, inherently, transphobic.

I once thought I was the ultimate trans ally, and I did not believe I had to work for it. I believed this because we live in a culture in which, if you merely accept what is deemed different, you are deemed to have done enough. And then, if you actually go to bat for a marginalized group, you will either be mocked for being a social justice warrior or lauded for being a social justice warrior. There’s something gross about this. Shouldn’t defending the basic rights of our fellow humans be understood as a simple contribution to our shared community and well-being?

•••

About eight years ago, I had a student who was far ahead of me in their understanding of these issues. This student was a gifted writer. To be honest, I found them very annoying, not least because they used they/them pronouns. They had adopted a male name, yet they wore eye makeup. This confused me, and I didn’t have time for it. I needed to know whether this student was male or female —not because I actually cared, but because I found it exhausting to interpret the gender cues.

Let’s call this student “Lee.” When Lee pointed out that I had misgendered them, I felt like they were playing the victim. They were constantly drawing attention to ways I’d affronted them. This struck me as narcissistic. You might say I even began to despise Lee because it always seemed they were trying to trip me up.

Fierce?

I thought I was politically astute, and even fairly radical, because I was a fierce feminist activist. I’d even co-founded a feminist nonprofit that brought national attention to gender disparity in my field! I truly did not know how myopic my brand of feminism was. While I would have weakly supported trans rights, the fact is I did not know much about trans folks at all.

Lee was simply trying to teach me.

As a writing teacher, I also found the pronoun situation an affront to my dedication to proper grammar. To use the plural “they” instead of “he/her” was, according to the rules, simply wrong. I lived by the guidelines of “proper” grammar and taught them. I wanted my students to aspire to concise and exacting language. But the fact is, language is organic and accommodating. Our language changes with our experiences. Language is one of most effective barometers of social and cultural change.

Being a stickler for “proper” grammar was, I now see, short-sighted. It was also elitist. I’m still invested in teaching my students how to write clearly. I just recognize that language can and will thwart convention to accommodate previously unacknowledged realities.

And I owe Lee an apology. Though I have no idea where they are now, this is part of that apology. I’m grateful for what they taught me.

•••

It didn’t happen on one of our walks. I don’t actually remember where we were when it happened, which suggests it must have been traumatic for me. But it was the opposite of traumatic for my kid. They told me they now used “they/them” pronouns. They were confident and direct. Within minutes, it seemed, my kid also changed their name. I was appalled. I’d chosen my child’s name with great deliberation. It was meaningful and beautiful. How could they discard it? It felt like a wound.

But while this seemed sudden to me, it had been a long time coming for JJ. Had I not noticed their interest in trans and nonbinary people (especially pop stars) and friends?

Casual transphobia

One of the biggest obstacles I experienced in the days and weeks after my child came out as trans was adjusting to using their new name and pronouns. I still trip up. But it has been far more difficult for JJ than it has been for me.

JJ has been going by “they/them” for nearly two years now, and they are still misgendered by peers at school. Being misgendered is painful for a trans person. If you have difficulty appreciating this, as I first did, consider how you would feel if someone constantly (and casually) referred to you by the wrong name. Perhaps you’ve been addressed by a nickname that makes you uncomfortable. Perhaps someone routinely mispronounces your name. It doesn’t feel good, does it? It’s disrespectful. This is how I came to understand that being misgendered, whether by the wrong pronouns or by one’s deadname, is a form of transphobia.

You know what else is a form of transphobia? Medical discrimination. I remain amazed by how difficult it was to find my child gender affirming care despite the fact that I’m a white, educated, upper middle class cisgender woman. I came up against obstacles everywhere I turned, from the therapist who claimed LGBTQ+ expertise but misgendered JJ, to the representative at the closest gender clinic who informed me JJ wouldn’t be eligible for puberty blockers until they were 16 (which, frankly, makes this treatment beside the point if your child hopes to avoid puberty in a body they are actively trying to escape).

I was lucky enough to find a doctor in a nearby state who would prescribe my kid blockers when they were 13. My kid stood taller immediately and spoke to peers and adults in an assured, relaxed manner. They started to smile more.

Joy

Here’s another thing you need to understand about being trans: it is not a tragedy. There is joy in it. There is pleasure in being in the right body, in being recognized as yourself.

It took a long time for me to actually understand any of this. I doubt I would have ever come to understand it if not for the one person I love most on earth being trans. I had to understand in order to know my child better and help get them what they needed. I had to listen and learn.

It hurts in the way being a parent always hurts: you see your kid out in the world, vulnerable, and you worry. What hurts most for me, and actually scares me enough to knock me out of sleep, is recognizing that trans folks are actively discriminated against in almost every aspect of their lives, from using the bathroom to shopping for clothes, from playing a sport to sleeping safely at summer camp.

For example, before I learned my child is trans, I had no idea bathrooms could be a challenge while running routine errands with my kid in tow. Several times a year—on a long drive, say, or a holiday shopping trip—almost every parent will find that getting their child to a public restroom has become their urgent and newfound mission in life. This simple goal becomes very complicated when one is faced with gendered restrooms and a child who feels unsafe going into the “Women’s Room” (where, if they appear masculine, they might be perceived as threatening) or the “Men’s Room” (into which their mother cannot escort them). Wouldn’t it be a relief if restrooms weren’t gendered?

There are a couple nongendered restrooms at JJ’s school, but they are hard to reach between classes and often dirty (JJ shared their theory that cishet boys urinate on the toilet seats and floors to intentionally defile this space). As a result, JJ doesn’t use the bathroom at school. They don’t drink much water or anything else, so they won’t have to use the restroom. But this means I have a dehydrated kid, and everyone knows that’s unhealthy.

Klonopin

But let’s talk about another sobering reason I was afraid to have a trans child: the harm that might come to them for being a trans citizen of this country. All parents fear for their children. But the parents of trans kids quickly learn that their children face adversity around every corner.

It’s not only all those hateful folks who are destroying the lives of trans people by taking away their right to use the restrooms that feel right to them, or denying them the medications that keep them in their right bodies. It’s also those seemingly liberal publications and their editors and contributors whose words we consume—the way they propagate trans hate while appearing harmless. The New York Times, my favorite news outlet, has lately had me reaching for the Klonopin.

Take a closer look at their articles and opinion pieces. You’ll find no trans people cited as sources or authorities. You'll find cis people who seem oddly invested in determining trans rights. I wonder what’s in it for them?

Pamela Paul, a Times opinion columnist, is a revealing example of someone who appears reasonable on the surface but slides her anti-trans agenda into my side like a knife. Last December, I was excited to dip into Paul’s piece about the 50th anniversary of the album Free to Be … You and Me. Its songs and skits embodied the dreams of the late 1960s and ’70s: we were all equal, feelings weren’t things to be ashamed of, and it was OK for boys to like dolls. The album and its companion book pressed against gender binaries, and I recalled the enormous relief my generation experienced by simply having these binaries questioned. There was one song in particular that I played over and over when I was a kid: “It’s All Right To Cry,” performed by Rosey Grier, the football player. “Crying gets all the mad out of you,” Rosey sang. Crying was my form of self-care.

Nostalgia

Coming across Paul’s column, I prepared to sink back into those groovy ’70s feelings. Who doesn’t appreciate a little nostalgia as a reprieve from the news? But what I thought would be a celebration of the album’s transgressive affirmations turned out to be an anti-trans sandwich with Free to Be as the bread.

Right in the middle, Paul argues that despite the social progress the record helped us achieve, “we risk losing those advances. In lieu of liberating children from gender,” she writes, “some educators have doubled down, offering children a smorgasbord of labels—gender identity, gender role, gender performance and gender expression—to affix to themselves from a young age.”

You know what makes me want to cry these days? People who think they know what is best for my kid without knowing my kid. People who think they have the right to make decisions that affect the lives of other people when they do not understand their circumstances. Politicians like Greg Abbott, Ron DeSantis, and Marjorie Taylor Greene, who have no understanding of the experience of trans folks and their loved ones and who seek to destroy the lives of trans children and their families because they are unwilling to open their minds and consider a lived experience different from their own.

We could speculate as to why Paul cares enough to write lengthy editorials about transgender people, or why she wrote 2,000 words in the Times defending anti-trans author J.K. Rowling, without even a passing mention of the increasingly devastating legislation trans folks wake up to every day. Does Paul fear that the category of woman could actually be merely a construct and, therefore, mutable? Is she under editorial orders? But let’s give Paul a break. Maybe she just doesn’t know. She doesn’t know how much it hurts to see the reality of your loved one denied in the pages of your newspaper.

Self and soul

My kid once described to me the feeling of gender dysphoria as a split between the soul and the self. A metaphysical nausea. When you know your child’s right to live as themselves is continually being denied, you feel nauseated, too. Your kid, who has never hurt anyone. And why must their true self be denied? Seriously, how does my kid being trans affect Pamela Paul or anyone else? It’s all right to cry. As the mother of a trans human, you can bet I cry!

To be the parent of a trans kid in our culture is to suffer for them and for yourself. One’s child is labeled deviant. You are labeled deviant for trying to support your child. You fear for your and your child’s physical safety (both of us are using pseudonyms here). Meanwhile, you try not to bring this up with your kid—even though they have no doubt read about the violence against trans youth and adults on their iPad—because your kid mainly likes to talk about their cats, Tinkerbell and Linus. Like any parent, you are happiest when your kid is calm and happy. So when do you talk to your kid about their safety? And what do you say?

That’s what’s hard about having a trans child. Other than that, they are the same as any other kid. Adorable, goofy, ornery, annoying, and sometimes wise beyond their years. Remember the day you brought your kid into the world? The newborn, unrecognizable yet, at the same time, utterly familiar. That was your kid. That will always be your kid.

When I gave birth to my kid, I couldn’t believe every single person I saw on the street had their very own mother. That every person you see was once someone’s baby. But this column is not just my story; it’s JJ’s. It’s a story about how a child changed their mother and made her better. And how this child made the world better for their mother.

I had a hard time coming up with a title for my project. My editor suggested we call it “Gender Free: Parenting a Trans Teen.” I asked JJ what they thought about that. Did they think of themselves as “gender-free?” Their response was adamant: “I’m not gender-free, I’m gender defiant.”

You can see just from that statement how my child changes my world every day. So Gender Defiant it is and shall be.